When I first collected the basic biographical details for your 10G grandparents Reverend John and Sarah Lyford, I noticed that everyone nearby on that branch of the family tree came from England, but John and Sarah came from Northern Ireland. I noticed that everyone else died in Massachusetts, as did Sarah in 1649, but John died in Virginia 15 years before her.

I thought “Well, that’s weird.” How did anyone from Northern Ireland get involved with the earliest New England immigrants, who hung out in very tight-knit congregations? Did Sarah remain in Plymouth while her husband took his ministry to Virginia?

Did I have the facts wrong?

Nope, I didn’t. The story of John and Sarah is fascinating for what it says about them and their lives; about the Pilgrims and their financiers; and about church fathers’ and historians’ respect for women both then and now.

To start

with, it’s important to remember the Plymouth Colony was created to serve two purposes: the Pilgrims wanted freedom to practice religion in their own way (rather than use the rites and beliefs prescribed by the Church of England), and their financiers, a London group called the Merchant Adventurers, wanted to make money--fishing, mining, farming, salt-making--they were not sure yet. In March 1624, the colony was in its fourth year, and had not yet turned a profit. The Pilgrims were dependent upon the Adventurers for supplies, bringing new settlers including tradespeople, and money. The partnership was delicate.

Some non-pilgrims, or “Strangers,” had come with the Pilgrims to the New World. Although religious tensions continued back in England, the strangers and the pilgrims were getting along well enough in Plymouth. The strangers had neither lived with the Pilgrims in the Netherlands nor joined their church, but they were not hostile to the Pilgrims’ religion—they knew the nature of the group with whom they had chosen to travel and live. For their part, the Pilgrim's insistence on separation of church and state wasn't just so they could worship as they pleased, but so they could allow the Strangers to worship separately or not at all, while not infiltrating the 'purity' of the Puritans' religion. It was a pretty stable arrangement.

Regardless

of how anyone wanted to worship, however, the

colony still had no ordained minister of any denomination in early 1624. The Pilgrims'

beloved minister, John Robinson, had remained in Holland with the majority of

the flock, planning to come later. The Adventurers had sent one Anglican

minister of their own choosing, who had not handled frontier hardships well and spent most of his time alone writing poetry in Latin. To no one’s dismay, he promptly returned

to England.

When the Lyfords arrived on the Charity in March 1624, Lyford made a good first impression. In the words of William Bradford, the Pilgrims’ governor and historian (edited to modern language):

The third eminent person on this ship was the minister, Mr. John Lyford. When (he) first came ashore, he saluted us with reverence and humility… and shed many tears, blessing God that had brought him to see our faces; and admiring the things we had done as if (he was) the humblest person in the world.

The Pilgrims, in turn "…gave him the best entertainment we could, in all simplicity, and a larger allowance of food out of the store than any other had. As I had used in all weighty affairs to consult with Elder Brewster, together with his assistants, so now we called Mr. Lyford also to counsel with us in the weightiest businesses."

But less than two years later, the colony was again without an ordained minister. The Pilgrims had expelled Lyford, who went to minister to Virginia colonists.

What happened? Through the eyes of some historians, a virtuous innocent minister was slandered and mistreated by the Pilgrim leaders, simply because he was Anglican. Here is Nathaniel Philbrick, writing in a 2006 New York Times bestseller Mayflower: A Story of Voyage, Community, War to make a point about the “mean-spirited fanaticism” of the Pilgrims:

Lyford “was cast out of the settlement for secretly meeting with disgruntled settlers who wished to worship as they had back in England. One of Lyford’s supporters, John Oldham, was forced to run through a gauntlet of Pilgrims who beat him with the butt ends of their muskets. In his correspondence, Bradford did his best to claim that Lyford and Oldham richly deserved their punishments. The Adventurers, however, chastised the Pilgrims for being “contentious, cruel, and hard-hearted, among your neighbors and towards such as in all points, both civil and religious, do not jump with you."

An even more

energetic defense of Lyford was offered in a paper submitted to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1928, by a Colonel Banks. (I’ve heavily edited this

excerpt; the original is wordy and repetitive):

Bradford's reaction to Lyford was one of unfeigned hostility from the day of his landing. All clergymen of the Church of England looked alike to him. Lyford was the victim of a whispering campaign, and (Bradford) tells his story in a detail all out of proportion to its real importance. In (Bradford’s account), we have only the unsupported word of a hostile writer motivated by a bitterness of spirit against anything or anybody who differed from him or his sect … (in which) … all the repulsive details rested on the supposed confession of a woman.

We have only Bradford's account of what happened in 1624-25. Within weeks of his arrival in Plymouth,

Lyford ceremoniously renounced the Church of England and joined the Pilgrims' church, at

which time the community accepted him as their minister, though there is no doubt they would have preferred Robinson. Lyford was then called to preach every Sunday to anyone in the colony who wished to attend services.

However, Lyford also continued to administer Anglican rites to those who requested them--something that aggrieved the Pilgrims, now that he had sworn an oath that he was a Puritan.

So when

Lyford was observed writing long letters back to the Adventurers shortly

before a boat left in early summer for London, Bradford intercepted and read

those letters. They were filled with allegations of mismanagement both large and small. Among other complaints, Lyford wrote that the Pilgrims were denying worship and even food to colonists who did not belong to their church; that they were refusing to conduct business with anyone who did not share their religious views; and that they were wasting the Adventurers' investment by doing things like leaving hoes in fields to rust. Lyford recommended that the Adventurers prevent passage of Rev. Robinson and send no more Pilgrims but instead send only loyal Anglican colonists, so that they would have a controlling majority. To add insult to injury, Lyford revealed that while on his passage to America, he himself had purloined some letters between Robinson and the colony's leaders, which Lyford quoted and ridiculed.

Without Lyford’s knowledge but with the cooperation of the ship's captain, Bradford copied some of the Lyford's letters before returning them to the London-bound mailbags, along with a letter of his own, refuting the allegations point by point.

Bradford told no one what he’d read and took no other action for several weeks, during which Lyford and Oldham did not bring any of their complaints directly to the colony’s leadership, but continued to hold their meetings and "become ever more perverse, with malicious carriage."

In midsummer, Lyford and Oldham crossed a line. They scheduled a public meeting on a Sunday in violation of the colony’s practice of reserving the Lord’s day for rest and worship. In Bradford’s words, this meeting was called for the dissidents “publicly to act what privately they had been plotting.”

Upon hearing of this meeting, Bradford called a pre-emptive meeting of the whole colony. Bradford accused Lyford and Oldham of attempting to undermine the colony by communicating false allegations of discontent and mismanagement to the Adventurers. Both Lyford and Oldham denied it. Bradford then pulled out the letters and read them to the entire assembly.

Oldham was enraged. Defiant, he said he and Lyford were reporting to London only what others had said to them and he called upon those men to support him. But everyone remained silent.

Lyford, in contrast, remained calm as his letters were read and discussed. The colonists he’d quoted admitted attending his meetings, but denied criticizing the colony, its religion, or its leaders. Finally, when Lyford was confronted with his duplicity in continuing to administer Anglican rites after having sworn conversion to the Pilgrims’ religion, he:

burst out into tears, and confessed he feared he was a reprobate, his sins were so great that he doubted God would pardon them, he was unsavory salt, and so forth. He said he had so wronged them that he could never make amends, confessed all he had written against them was false in both matter and manner. And all this he did with as much fullness as words and tears could express.

Lyford said that henceforth he would “go minister the (Anglican) sacraments without ever speaking a word unto them, either as magistrates or brethren.”

The colonists then voted to expel both Oldham and Lyford—Oldham immediately, and Lyford was given six months to either prove himself truly repentant and worthy, or to arrange passage for himself and his family and leave.

Lyford used this reprieve to “carry himself well and to prove his repentance sound.” He publicly confessed his sin in the church, acknowledging "he had done very evil, and slanderously abused them; and … that if God should make him a vagabond in the earth, as was Caine, it was just, for he had sinned in envy and malice against his brethren as he did. He confessed the causes of his doings to be pride, vainglory, and self love."

As a result, some Pilgrims “began again to conceive good thoughts of him … and admitted him to teach amongst them as before. Deacon Samuel Fuller and some other tender-hearted men were so taken with his signs of sorrow and repentance, they professed they would fall upon their knees to have his censure released.”

Back in London, however, the Adventurers had undertaken a belated quasi-judicial checking of Lyford’s references. In Bradford’s modernized words:

(Upon receiving Bradford’s and Lyford’s letters), some of Lyford’s friends held it a great scandal that a man so godly and esteemed should be treated like this, and they threatened to sue. The Adventurers referred the matter to a further meeting to conduct an inquiry before deciding the matter. They chose two eminent men as moderators: Lyford’s faction chose Mr. White, a counselor at law, and the other side chose Rev. Hooker.

The colonists’ representative, Edward Winslow, had inquired in Ireland and reported to the Adventurers that two godly and grave witnesses were willing to testify under oath, if called, that among Lyford’s congregation there had been a godly young man who had cast his affection on a maid. But desiring to know the Lord’s will before proposing marriage, he sought Rev. Lyford’s advice and judgment of this maid. Lyford arranged to meet with her several times in private conference and in conclusion commended her highly to the young man as a very fit wife. The two were married, but the woman was much troubled, afflicted in conscience, and did nothing but weep and mourn. Before long, her husband was able to get her to tell him what had happened.

Begging him to forgive her, she said Lyford had overcome her and defiled her before marriage. These things being thus discovered, the woman’s husband took some godly friends to deal with Lyford for this evil. Lyford confessed it with a great deal of seeming sorrow & repentance, but was forced to leave Ireland partly for shame and partly for fear of further punishment.

As the time for Lyford's banishment drew near, his wife Sarah had been so eaten up with guilt, grief, and worry that she could stay silent no longer. Again,

Bradford’s is the only account we have, and again, I’ve heavily edited this

excerpt for length and vocabulary:

Sarah “could no longer conceal her grief and sorrow. She feared the great judgment of God would fall upon herself and her family for her husband’s conduct. She feared that she might fall into the Indians’ hands and be defiled by them as her husband had defiled other women, in the manner that God had threatened David’s wives would be defiled as punishment for his sins in 2 Samuel 12:11.

She opened first to some of her friends and to a deacon of the church. She informed them that before she’d married Lyford, she’d been told that he had fathered a child out of wedlock. When she confronted him and turned him away, he not only stiffly denied it but took a solemn oath that the tale was untrue.

Upon which she gave consent and married him, but soon afterwards the child’s mother brought the baby to them. She then confronted him with his false oath, but he begged her forgiveness, saying that if he had not taken that oath, she would not have married him.

During their marriage since, she has been unable to keep domestic help because he would be meddling with them, and sometimes she has caught him in the act, with such other circumstances as I am ashamed to relate.

Being a grave matron and of good carriage, she spoke these things out of the sorrow of her heart, sparingly but with even further intimations. That which seemed most to affect her was to see his former conduct in his recent repentance—how he would shed tears, and use great and sad expressions, and yet afterwards fall into the same conduct again.

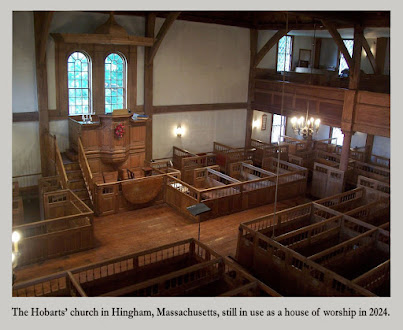

Lyford left the colony with some of the disgruntled colonists, first to a northern outpost (later named Salem) and then to Virginia, where he assumed the pulpit first at a location known as Martin's Hundred and later at another location known as Shirley's Hundred, where he died.The Pilgrim community rallied around Sarah and her children. As soon as word came of Lyford's death, Sarah remarried with the widower Edmund Hobart, a respected community elder in Hingham, and father of its esteemed pastor, Peter Hobart. (Coincidentally, Edmund is your 11G grandfather through his daughter, Nazareth.) The Hobart family assisted the Lyford children in obtaining their inheritance from their father after his death.

After reading the whole story from several sources, I know what I believe. This was real life, so we cannot assume anyone is wholly innocent and wise. Yes, the Pilgrims exhibited a "mean-spirited fanaticism" in some situations. Yes, the Anglican Church failed to defrock a clergyman who had admitted sexual misconduct. Yes, the Adventurers were disdainful and careless to the point where they sent an unvetted clergyman to the vulnerable young colony.

I can see an honest historian compiling evidence to illustrate any--or better yet, all--of those points. But Lyford's story belongs on the pile of facts that support and justify the Pilgrims. This isn't a story of their religious intolerance; it's a story of their wisdom in resisting Anglican imperiousness.

While there is no doubt that the Pilgrims did not seek Anglican clergy presence in Plymouth Colony, they were aware that Lyford was a fully credentialed and ordained Church of England representative as soon as he got off the boat. They did not tell him to get back on. Instead, he was allowed to meet privately with whomever he chose. The Pilgrims knew he would administer Anglican baptisms, perform Anglican weddings, and conduct Anglican services for those colonists who wanted them. They were willing to tolerate all that.

What they couldn't tolerate was Lyford lying about his conversion to their faith and then, as a Puritan minister, performing Anglican rites. What they couldn't tolerate was Lyford withholding his criticism from them while expressing it to their financiers. And finally, when the colony was ready to forgive Lyford of those admitted sins, they would not tolerate sexual misconduct.

Perhaps the most important message in this story, however, isn't about either Puritanism or Anglicanism. Every ugly story Bradford tells about Lyford is consistent with a personality type I recognize, an archetype our modern culture still struggles with.

Lyford fits the pattern of a sociopath who perceives that "it was the only way to get what I want" is sufficient reason for lying and manipulation; one who takes advantage of the entitlements that society bestows upon men of education or wealth, one who pursues a career that puts him in a position of power over others and enables a life of relentless self-gratification without accountability for the damage he does to his victims.

I am thankful that at least two of Lyford's congregations--the one in Armaugh and the one in Plymouth--believed the "supposed confessions" of the unnamed young bride and your 10G grandmother Sarah and then removed Lyford from a position of authority.

I also notice the apparently enduring practice of church fathers moving sexual predators around, allowing them to escape legal prosecution everywhere. Then and now, they choose to "rest quietly" even when they are finally convinced of their subordinates' predatory behavior.

As for the historians, I'd like to excuse those writing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They were still eulogizing President Lincoln and loathe to repeat unflattering information about his 4G grandfather. The author of the 1928 historical report I quoted earlier was explicit in a postscript: He had been working on Lincoln's genealogy when he recognized Lyford as the clergyman so heavily criticized in Bradford's History of Plymouth Plantation and felt the need to defend him. (I do notice, though, that he didn't seem to mind denigrating Sarah, whose relation to Lincoln was equal to John's.)

I can't find any sympathy, however, for modern historians who treat Lyford's sexual misconduct as trivial or who fail to mention it at all. Eager to tell a story about the Pilgrims' failure to protect Anglican clergy, they find little of interest in their commitment to protecting women.

No comments:

Post a Comment